Phonological concepts are touched upon in this section only when they are relevant for the grammar. For more in-depth studies, the following works are recommended:

- ثمره، یدالله. آواشناسی زبان فارسی – آواها و ساخت آوایی هجا. چاپِ یکم، تهران: مرکز نشر دانشگاهی، ۱۳۶۴.

- باقری، مهری. واجشناسی تاریخی زبان فارسی. چاپِ یکم، تهران: نشر قطره، ۱۳۸۰.

The transcription follows to the rules of the “International Phonetic Association” = IPA, with the Persian part delivered by Prof. Dr. Elmar Tendes and Dr. Mohammad Reza Majidi from the “Institut für Phonetik, Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaften and Indogermanistik der Universität Hamburg”:

Journal of the International Phonetic Association 21 (1991), 96-98. (repaint in: Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge: University Press 1999, S. 124-125).

This analysis refers only to the educated Persian speakers in the Tehran area. Therefore, our work uses some additional characters of the “International Phonetic Alphabet” to reflect the standard languages of Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and archaic idioms of Persian as well.

The older transliteration “Americanist phonetic notation” = APA is largely displaced by IPA, however, it is found in many standard works from the USA (particularly in Encyclopædia Iranica).

| Contents |

|---|

a. Phonemes

A phoneme is the smallest segment of speech that distinguishes its meaning. It is object of investigation of phonology. Phonemes are stated between two slashes, e.g. /m/ or /o/.

Phonemes are strictly abstract classes of phones ↓. However, they fulfill grammatical purposes normally so that a substantiated phone reconnaissance becomes superfluous.

The following phonemes can be found in Persian speech:

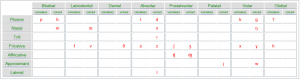

a•a. Consonants

A consonant is a phoneme whose articulation narrows so that the stream of breath is blocked completely or partially. The common sign for a consonant is c.

Note the Persian consonants in the table below:

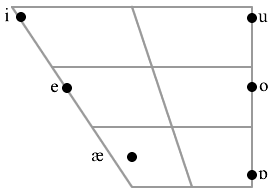

a•b. Vowels

A vowel is a phoneme whose articulation flows largely unhindered. The common sign for a vowel is v.

See the Persian vowels in the diagram below. The vowels /ɒ/, /i/ and /u/ are normally pronounced with elongatation (see combinative variation ↓): /ɒː/, /iː/, /uː/

b. Phones and Allophones

A phone is the smallest phonetic unit in speech. It is object of investigation of phonetics. Phones are stated between brackets, e.g. [m] or [o].

Within a language, phonemes can appear in the form of several phones (e.g. in different dialects) without the meaning of the content changing (= variation), e.g. [æ] and [e] in /kæʃti/ ⇆ /keʃti/ کشتی. Alternative phones are called allophones.

Variations are subdivided as follows:

b•a. Combinative Variation

The term combinative variation describes the case when a phoneme adopts different pronunciations depending on the surrounding phonemes:

-

In the archaic Persian (until the Mongolian era), the phoneme /d/ د appeared in the form of the allophone [ð] ذ (voiced dental fricative), when it followed after a vowel:

زیرا که آن سرایزذ /sær-izæð/ست کی بذ /bæð/ آن آگاه کنذ /konæð/ آن کس را خواهذ /xvɒhæð/ از اولیاءِ او.

Abu Yaghub Sagzi (10th Century AD)

This combinative variation does not exist in the modern Persian, and the allophone [ð] ذ appears generally as allophone [d] د. A few examples have kept the diction ذ, but with the pronunciation [z]:

پذیرفتن /pæziroftæn/، گذشت /gozæʃt/

- The following combinative variations exist in the modern Persian idioms:

- The replacement of the normally long vowels /ɒː/, /iː/ and /uː/ with the short allophones [ɒ], [i] and [u] when preceding the consonant /n/, if this consonant is located with the vowel in the same syllable ↓:

زمان /zæ.mɒn/ ⇆ زمانه /zæ.mɒː.ne/

رساند /ræ.sɒnd/ ⇆ رسانا /ræ.sɒː.nɒː/

سیمین /siː.min/ ⇆ سیمینه /siː.miː.ne/

خون /xun/ ⇆ خونین /xuː.nin/

- The replacement of the consonant /m/ when preceding the consonants /f/ and /v/ with the allophone [ɱ] (voiced labiodental nasal): /hæɱfekr/ همفکر, /hæɱvæzn/ هموزن

- The replacement of the consonant /n/ when preceding the consonants /g/ and /k/ with the allophone [ŋ] (voiced velar nasal): /sæŋgær/ سنگر, /koŋkur/ کنکور

- The replacement of the consonant /n/ when preceding the consonant /ɣ/ with the allophone [ŋ̠] (distal voiced velar nasal): /meŋ̠ɣɒr/ منقار

- The replacement of the consonant /n/ when preceding the consonant /b/ with the allophone [m]: /æmbɒn/ انبان, /ʃæmbe/ شنبه

- The replacement of the vowel /æ/ when preceding the consonant /j/ with the allophone [e]. This combinative variation is noted in modern, more western idioms (particularly in the standard language of Iran), but it is largely absent in the archaic and the modern, more eastern idioms of Persian (mainly the standard languages of Afghanistan and Tajikistan): /kæjhɒn/ ⇆ [kejhɒn] کیهان, /ʃæjpur/ ⇆ [ʃejpur] شیپور

- In the stems of dental suffixes (/-t/, /-tæn/ and /-tɒr/), long vowels can be replaced with their shorter allophones, both preceding voiceless fricative consonants (in Persian /f/, /s/, /ʃ/, /x/ and /h/) and voiced alveolar consonants (in Persian: /d/, /n/, /r/, /z/ and /l/):

- The replacement of the vowel /ɒ/ with the allophone [æ]:

آراست /ɒrɒst/ ⇆ آرست /ɒræst/، اوانید /ævɒnid/ ⇆ اونید /ævænid/

انباریدن /ænbɒridæn/ ⇆ انبریدن /ænbæridæn/، پالیدن /pɒlidæn/ ⇆ پلیدن /pælidæn/

- The replacement of the vowel /i/ with the allophone [e]:

ریشت /riʃt/ ⇆ رشت /reʃt/، آویخت /ɒvixt/ ⇆ آوخت /ɒvext/، ستیزید /setizid/ ⇆ ستزید /setezid/

فریفتن /feriftæn/ ⇆ فرفتن /fereftæn/، استیهیدن /estihidæn/ ⇆ استهیدن /estehidæn/، بخچیزیدن /bæxʧizidæn/ ⇆ بخچزیدن /bæxʧezidæn/

- The replacement of the vowel /u/ with the allophone [o]:

آشوفت /ɒʃuft/ ⇆ آشفت /ɒʃoft/، دوخت /duxt/ ⇆ دخت /doxt/

شنودن /ʃenudæn/ ⇆ شندن /ʃenodæn/، آشوردن /ɒʃurdæn/ ⇆ آشردن /ɒʃordæn/

The variation preceding other consonants is very unusual, and is only used owing to metrical conformation:

آشامیدن /ɒʃɒmidæn/ ⇆ آشمیدن /ɒʃæmidæn/، فریبیدن /feribidæn/ ⇆ فربیدن /ferebidæn/

- The replacement of the vowel /ɒ/ with the allophone [æ]:

- The replacement of the normally long vowels /ɒː/, /iː/ and /uː/ with the short allophones [ɒ], [i] and [u] when preceding the consonant /n/, if this consonant is located with the vowel in the same syllable ↓:

b•b. Free Variation

Free Variation describes the case when a phoneme can appear in several allophones (often in different idioms of a language). It is typically inherited from Middle Persian, but in the following cases it occurred in the modern, more western idioms (particularly in the standard language of Iran); the archaic and the modern, more eastern idioms of New Persian (mainly the standard languages of Afghanistan and Tajikistan) usually have an identical pronunciation:

- The replacement of the long vowel /eː/ with the allophone [iː]: /heːʧ/ ⇆ [hiːʧ] هیچ, /ɒreː/ ⇆ [ɒriː] آری

- The replacement of the long vowel /oː/ with the allophone [uː]: /roːj/ ⇆ [ruːj] روی, /soːxtæn/ ⇆ [suːxtæn] سوختن

- The replacement of the vowel /æ/ with the allophone [e], if it is located at the end of a morpheme: /kuːræ/ ⇆ [kuːre] کوره, /guːʃæ/ ⇆ [guːʃe] گوشه

- The replacement of the phoneme string /æv/ with the allophone [ow], if these two phonemes are placed within the same syllable ↓: /æv.ræng/ ⇆ [ow.ræng] اورنگ, /sævt/ ⇆ [sowt] صوت, /ræv.ʃæn/ ⇆ [row.ʃæn] روشن, /næv/ ⇆ [now] نو, /ræh-ræv/ ⇆ [ræh-row] رهرو

Counter-examples: /ʤæ.vɒn/ جوان, /mi.ræ.væm/ میروم

In this case, if the consonant /w/ is presented at the end of a noun phrase or an adjectival phrase and becomes a syllable onset ↓ by attaching a suffix or an enclitic, it is replaced with the allophone [v]:

/næ.vin/ ⇆ [no.vin] نوین (from the adjectival phrase /næv/ ⇆ [now] نو)

/ræh-ræ.vɒn/ ⇆ [ræh-ro.vɒn] رهروان (from the nominalized adjectival phrase /ræh-ræv/ ⇆ [ræh-row] رهرو)

/pær.tæ.v-æʃ/ ⇆ [pær.to.v-æʃ] پرتوش (from the noun phrase /pærtæv/ ⇆ [pærtow] پرتو)

- The replacement of the vowel /ɒ/ at the beginning of stems of dental suffixes (/-t/, /-tæn/ and /-tɒr/) with the allophone [æ]:

آبشت /ɒbeʃt/ ⇆ ابشت /æbeʃt/، آوردید /ɒværdid/ ⇆ اوردید /æværdid/

آغالیدن /ɒɣɒlidæn/ ⇆ اغالیدن /æɣɒlidæn/, آژندیدن /ɒʒændidæn/ ⇆ اژندیدن /æʒændidæn/

The variations are only taken into account for the transcription in this website if it is useful to the idiom reconnaissance. It is the case for free variations, and the combinative variation of /d/ ⇆ [ð].

Specifically, the long vowels /ɒː/, /iː/ and /uː/ are transcribed always in the form /ɒ/, /i/ and /u/.

c. Syllable

A syllable is the smallest phoneme string that is pronounced promptly.

Each modern Persian syllable consists of a vowel which represents the syllable nucleus. One single consonant (= syllable onset) can optionally be placed in front of the syllable, and one or two consonants (= syllable coda) can follow the syllable.

Accordingly, Persian syllables can present the following syntaxes:

- v, e.g. /u/ او

- vc, e.g. /ɒb/ آب

- vc1c2, e.g. /æsb/ اسب

- cv, e.g. /pɒ/ پا

- c1vc2, e.g. /dur/ دور

- c1vc2c3, e.g. /ʃæst/ شست

In Middle Persian the syllable onset could also consist of two consonants (e.g. in /spær/, in New New Persian /se.pær/ سپر). The syllable onset /xv/ persisted in archaic idioms of New Persian, therefore the following syllable syntaxes additionally existed:

- c1c2v, e.g. /xvɒ.hær/ خواهر

- c1c2vc3, e.g. /xviʃ/ خویش

- c1c2vc3c4, e.g. /xvɒst/ خواست

The phoneme string /xv/ is replaced entirely in Persian by the consonant /x/: /xɒ.hær/, /xiʃ/, /xɒst/

The phonotactics of a particular language refers to specific description of which phonemes (or phones) can be combined within a syllable (or in a syllable string).

If a syllable which does not have an onset is placed in front of another syllable (having a coda), the last consonant of the first syllable becomes the onset of the second. This leads to the occurence of a syllable spreading on several morphemes, e.g. in /dæ.bir/ + /es.tɒn/ → /dæ.bi.res.tɒn/ دبیرستان.

As presented in these examples, syllable borders can be marked through points in IPA.

d. Sandhi

Sandhi (Sanskrit: संधि, from /san/ = “each other” and /dhi/ = “put”: “joining”) is an Old Indian grammar term. It describes systematic modifications (adding or omitting phonemes or phones, or changing the place of their articulation), which result from the coincidence of morphemes, to ease the pronunciation:

Sandhis can be classified as follows:

d•a. Epenthesis

One of the most commonly used types of sandhi in Persian is the insertion of a phoneme or a phoneme string between two morphemes, usually to facilitate their pronunciation. Such a phoneme or phoneme string is called epenthesis, which has, in contrast to interfix, no semantic function:

- One of the most predominant applications of epentheses is to avoid the following constellations:

- c1c2c3

- vc1c2, whereas v represents one of the long vowels /ɒ/, /i/ or /u/.

The epenthesis /e/ is commonly used in this case, seldom also the epenthesis /æ/:

پارسنگ /pɒrsæng/ ⇆ /pɒresæng/، رستگار /ræstgɒr/ ⇆ /ræstegɒr/، پیرمرد /pir-mærd/ ⇆ /pire-mærd/، شادمان /ʃɒd-mɒn/ ⇆ /ʃɒde-mɒn/، آموزگار /ɒmuzgɒr/ ⇆ /ɒmuzegɒr/, مهربان /mehrbɒn/ ⇆ /mehræbɒn/

The usage of epenthesis is optional here, and depends mainly on the idiom.

If consonant /j/ is the final phoneme of the constellation c1c2c3 the epenthesis /i/ is applied: /ʃæhrjɒr/ ⇆ /ʃæhrijɒr/ شهریار

- In addition, the following epentheses are applied, if the dental suffixes (/-t/, /-tæn/ and /-tɒr/) are attached to present participles (occasionally also to past participles, see 12•۱•a.):

- There is no phonetic limit to use the epenthesis /i/. Therefore, it is the most applied epenthesis with these suffixes:

بافت، بافید /bɒft/, /bɒfid/، نازید /nɒzid/

گساردن، گساریدن /gosɒrdæn/, /gosɒridæn/، پریدن /pæridæn/

خریدار /xæridɒr/

- The epenthesis /ɒ/ is applied only after the consonants /h/, /t/ and /d/:

رهاد /ræhɒd/، ایستاد /istɒd/

نهادن /nehɒdæn/، فرستادن /ferestɒdæn/، دادن /dɒdæn/

- The epenthesis /s/ can appear as the following allomorphs:

- As the allophone [s] after vowels:

آراست /ɒrɒst/، زیست /zist/

نشاستن /neʃɒstæn/، ریستن /ristan/

If the present participle ends with the vowel /u/, this vowel must be assimilated ↓ into [o]:

/ʃu/ + dental suffix /-t/ → /ʃost/ شست

/ʤu/ + dental suffix /-tæn/ → /ʤostæn/ جستن

/ru/ + dental suffix /-tæn/ → /rostæn/ رستن

In front of this epenthesis, the consonant /h/ must be elided ↓ from the final phoneme string /ɒh/, /æh/ and /ih/:

/ʤæh/ + dental suffix /-t/ → /ʤæst/ جست

/kɒh/ + dental suffix /-t/ → /kɒst/ کاست

/ʤih/ + dental suffix /-tæn/ → /ʤistæn/ جیستن

- As the allophone [es] after consonants:

/neh/ + dental suffix /-t/ → /nehest/ نهست

/dɒn/ + dental suffix /-tæn/ → /dɒnestæn/ دانستن

/jɒr/ + dental suffix /-tæn/ → /jɒrestæn/ یارستن

- After the consonant /r/, the allophone [is] can also be applied:

/negær/ + dental suffix /-tæn/ → /negæristæn/ نگریستن

- As the allophone [s] after vowels:

The application of epentheses is required after plosives (in Persian: /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/ and /ʔ/):

تابید /tɒbid/، خندید /xændid/، آهنگید /ɒgængid/، افتاد /oftɒd/

مکیدن /mækidæn/، گفتیدن /goftidæn/، بلعیدن /bælʔidæn/

- There is no phonetic limit to use the epenthesis /i/. Therefore, it is the most applied epenthesis with these suffixes:

- The epenthesis /ɒj/ can be used with the suffix /-ɒn/ after some monosyllabic present participles (see 20•۲•c.).

- Possessive pronouns appear in Persian (like in Greek) exclusively as enclitics. They are normally accompanied by epentheses /æ/ or /e/: /dæftær-æm/ دفترم, /bærɒdær-eʃɒn/ برادرشان

Also in certain cases, other epentheses can be used with possessive pronouns, as described in chapter 7•۲•a..

- Other epentheses consisting of vowels are very seldom and non-productive, for example the epenthesis /i/ in the following affixal formations:

/sɒl/ + suffix /-ɒn/ → /sɒliɒn/ سالیان

/mɒh/ + suffix /-ɒn/ → /mɒhiɒn/ ماهیان

- Several consonants are used as epentheses, when two vowels directly follow each other, for example:

- Epenthesis /j/ in /mæjɒzɒr/ میازار and /færdɒ-je keʃvær/ فردایِ کشور

- Epenthesis /g/ in /mæsxærægi/ مسخرگی and /sæjjɒrægɒn/ سیّارگان

- Epenthesis /k/ in /niɒkɒn/ نیاکان and /kɒnɒki/ کاناکی

- Epentheses /vv/ and /jj/ in /sevvom/ سوم and /dojjom/ دیم

- Epenthesis /v/ in /donjɒvi/ دنیاوی and /mɒnævi/ مانوی

- Epenthesis /ʤ/ in /sæbziʤɒt/ سبزیجات and /tælɒʤɒt/ طلاجات

- Epenthesis /h/ in /ɒɣɒ-he/ آقاهه and /bæʧʧe-he/ بچّههه

d•b. Elision

Elision is the omission of a phoneme or phoneme string, for example:

- Intensive pronoun /hæm-/ + /mɒnænd/ → /hæmɒnænd/ همانند

- /bu/ + suffix /-estɒn/ → /bustɒn/ بوستان

- Prefix /be-/ + present participle /neʃin/ → /benʃin/ بنشین

d•c. Assimilation and Dissimilation

Assimilation is a process which matches the distinctive features of one phoneme to another near phoneme. In the Persian derivation, the assimilation is noted in the following cases:

- Anticipative assimilation. In this form, the first phoneme is adapted to the second one:

Prefix /be-/ + present participle /koʃ/ → /bekoʃ/ ⇆ /bokoʃ/ بکش

Prefix /be-/ + present participle /jɒb/ → /bijɒb/ بیاب

- Perseverative assimilation. In this case, the second phoneme adopts the distinctive features of the first one:

present participle /kɒv/ + suffix /-eʃ/ → /kɒveʃ/ ⇆ /kɒvoʃ/ کاوش

The most prominent example for the perseverative assimilation in Persian is the sonorization of the voiceless consonant /t/ in the dental suffixes (/-t/, /-tæn/ and /-tɒr/) to the voiced allophone [d] after voiced consonants or vowels:

زد /zæd/، آماد /ɒmɒd/، شد /ʃod/، سود /sud/

کندن /kændæn/، آماردن /ɒmɒrdæn/، آژدن /ɒʒdæn/، آمیغدن /ɒmiɣdæn/

کردار /kærdɒr/، خریدار /xæridɒr/

Dissimilation is noted in the Persian derivation only anticipatively and for vowels. In this case, a vowel becomes less similar to the next one:

prefix /be-/ + present participle /ændɒz/ → /biændɒzʃ/ بیانداز

/mɒni/ + suffix /-i/ → /mɒnævi/ مانوی

d•d. Metathesis

Metathesis is a sandhi that alters the order of phonemes:

/gol/ + suffix /-estɒn/ → /golestɒn/ ⇆ /golsetɒn/ گلستان

prefix /be-/ + present participle /gosæl/ → /begosæl/ ⇆ /bogsæl/ بگسل

d•e. Diphthongization and Monophthongization

The process of building diphthongs from monophthongs in the derivation is called diphthongization:

prefix /nɒ-/ + /omid/ → /nævmid/ نومید

The replacement of diphthongs with monophthongs is called monophthongization:

/bu/ + suffix /-estɒn/ → /bostɒn/ بستان

e. Mutation

One encounters a mutation if a sound change is fulfilled in the derivation of one morpheme from another (the so-called “internal derivation”). Mutation is noted typically in the derivation of non-finite verb forms in the Indo-European languages.

Mutation processes are classified and described as follows:

e•a. Apophony (Indo-European Ablaut)

Apophony or Indo-European ablaut names the vowel change within a flectional paradigm in Indo-European languages. This occurence was described in 1819 by the German linguist, Jacob Grimm, and in Persian can be found in these forms:

- the derivation of present participles from verbal roots:

- Ablaut of the final vowel /u/ to the diphthong /æv/ after the consonant /n/:

/ʃenu/ → /ʃenæv/ شنو

/ɣonu/ → /ɣonæv/ غنو

/bæxnu/ → /bæxnæv/ بخنو

- Ablaut of the final vowel /u/ to /ɒ/ in all other cases, if the verbal root is polysyllabic:

/ɒzmu/ → /ɒzmɒ/ آزما

/goʃu/ → /goʃɒ/ گشا

/færmu/ → /færmɒ/ فرما

- Ablaut of the final vowel /u/ to the diphthong /æv/ after the consonant /n/:

- Ablaut of the phoneme strings /ær/ and /or/ to /ɒr/ in the derivation of nominal participles from verbal roots:

/kær/ → /kɒr/ کار

/bor/ → /bɒr/ بار

/xor/ → /xɒr/ خوار

- Ablaut of the final vowel /ɒ/ to /un/ in the derivation of nominal participles from present participles:

/æfsɒ/ → /æfsun/ افسون

/æfzɒ/ → /æfzun/ افزون

/ɒzmɒ/ → /ɒzmun/ آزمون

/nemɒ/ → /nemun/ نمون

/sɒ/ → /sun/ سون

e•b. Grammatical Alteration according to Verner’s Law

In 1875, the Danish linguist Karl Verner expressed the syntax voicing of voiceless fricative consonants (in Persian /f/, /s/, /ʃ/, /x/ and /h/) in the internal derivation of Indo-European languages, which he traced back to the Proto-Indo-European language; it is generally referred to as Verner’s Law.

The consonant change within a flectional paradigm in Indo-European languages according to Verner’s low is termed grammatical alteration. In Persian it can be noted in the derivation of present participles from verbal roots:

- Grammatical alteration of the final fricative /x/ to /nʤ/ after the vowel /æ/:

/sæx/ → /sænʤ/ سنج

/ælfæx/ → /ælfænʤ/ الفنج

- Grammatical alteration of the final fricative consonant /x/ to /z/ after the long vowels /ɒ/, /i/ and /u/:

/sɒx/ → /sɒz/ ساز

/gorix/ → /goriz/ گریز

/æfrux/ → /æfruz/ افروز

- Grammatical alteration of the final fricative consonant /ʃ/ to /r/ after the vowel /ɒ/:

/dɒʃ/ → /dɒr/ دار

/gomɒʃ/ → /gomɒr/ گمار

/kɒʃ/ → /kɒr/ کار

- Grammatical alteration of the final fricative consonant /s/ to /n/ or /nd/ after the vowel /æ/:

/ʃekæs/ → /ʃekæn/ شکن

/ɒɣæs/ → /ɒɣæn/ آغن

/bæs/ → /bænd/ بنـد

/pæjvæs/ → /pæjvæn/, /pæjvænd/ پیون، پیونـد

- Grammatical alteration of the final fricative /f/ to /b/ after the long vowels /ɒ/, /i/ and /u/:

/jɒf/ → /jɒb/ یاب

/ferif/ → /ferib/ فریب

/ɒʃuf/ → /ɒʃub/ آشوب

- Present participles are generated from verbal roots ending with the vowel /i/, /e/ or /æ/ by means of attaching the consonant /n/. The assumption suggests that these verbal roots ended originally with a weak fricative /h/ which is replaced by the consonant /n/ by means of grammatical alteration:

/ɒfærih/ → /ɒfærin/ آفرین

/ʧih/ → /ʧin/ چین

/ʧeh/ → /ʧen/ چن

/zæh/ → /zæn/ زن

f. Reduplication

Reduplication is a sound change process in the first syllable of a phrase (reduplicational focus) to derivate a new element reduplicate) without any independent meaning. In Persian, noun and adjectival phrases act as reduplicational focuses.

Reduplicates accompany their focuses in the following forms, in order to adapt their meaning to their environment or similar terms:

- Copulative composition (see 9•b.)

- Copulative coordination with the conjunction /o/ و (see 9•a•a.)

Reduplication can appear in Persian in the following ways:

- Replacing the initial consonant of the reduplicational focus with the consonant /m/:

کتابمتاب /ketɒb-metɒb/، حاجیماجی /hɒʤi-mɒʤi/، جاهلماهل /ʤɒhel-mɒhel/، تار و مار /tɒr o mɒr/

تازهمازه /tɒze-mɒze/ خدمتِ شما چیست؟

آی از آن چون چراغ پیشانی!

آی از آن زلفکِ شکست و مکست /ʃekæst o mekæst/!

Rudaki (9th and 10th Century AD)

تا به اکنون چیز و میزی /ʧiz o miz/ داشتیم

زآن که در عشرت نباشد زو گریز

Anvari (12th Century AD)

- Replacing the initial consonant of the reduplicational focus with the consonant /p/:

خرت و پرت /xert o pert/، چرندپرند /ʧærænd-pærænd/، ساخت و پاخت /sɒxt o pɒxt/

کارها خیلی شلوغپلوغ /ʃoluɣ-poluɣ/ شده.

وقتست کهاز فراقِ تو و سوزِ اندرون

آتش در افکنم به همه رخت و پختِ /ræxt o pæxt/ خویش

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- Replacing the first vowel of the reduplicational focus with the vowel /u/:

چالهچوله /ʧɒle-ʧule/، لات و لوت /lɒt o lut/، تک و توک /tæk o tuk/

- Irregular modification of the initial consonant in the reduplicational focus:

قلنبهسلنبه /ɣolonbe-solonbe/، دریوری /dæri-væri/، دنگ و فنگ /dæng o fæng/، اخم و تخم /æxm o tæxm/