One should distinguish between determinative phrases and attributes. Both acompany other phrases to describe them in great depth, but attributes have no particular phrase class and can appear in the form of the following phrases:

- Noun phrases: /næsl-e mæn/ نسلِ من, /færib-xordæn/ فریبخوردن

- Adjectival phrases: /zæn-e zibɒ/ زنِ زیبا, /bozorg-dɒʃt/ بزرگداشت

- Adverb phrases: /bær-xɒstæn/ برخاستن, /bɒz-tɒb/ بازتاب

- Adpositional phrases: /ɒmædæn-e be tehrɒn/ آمدنِ به تهران, /sær be zir/ سر به زیر

- Inflectional phrases: /væɣt-i to ɒmædi/ وقتی تو آمدی, /ɒn ʧe didid/ آن چه دیدید

The phrase which is attributed is termed attributive focus in this website.

The attribution of nomina actionis, nomina patientis and nomina agentis and the relative clauses are detailed in Chapters 3•d•a•b., 4•۱•b., 4•۲•b. and 18•۱.. The following forms of attribution are analyzed in this chapter:

| Contents |

|---|

a. Appositions

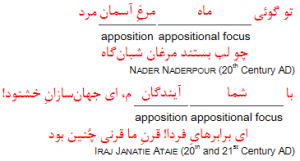

One notes a promitive from of attribution in cases when the attribute (= apposition) follows its focus(= appositional focus) directly, to explain it in greater depth. Both constituents of such a phrase are noun phrases:

As these examples highlight, in Persian there is an appositional concord in the number: The apposition and its focus are in the same subcategory of number (singular or plural).

One prominent feature of Persian language is the application of intensive pronouns as appositions (see 7•۳•a.):

بیمارستانِ ما پنج ساختمان دارد، و هر ساختمان خودش از چند بخش تشکیل شده.

او خودش میتواند کفشش را بپوشد.

تو بندگی چو گدایان به شرطِ مزد مکن!

که خواجه خود روشِ بندهپروری داند

Hafez (14th Century AD)

تو چه ارمغانی آری که به دوستان فرستی؟!

چه از این به ارمغانی که تو خویشتن بیایی؟!

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

b. Genitive

Genitive is a kind of phrase syntax that sets two constituents in a hierarchical relationship (normally using the enclitical conjunction /-e/).

The superordinate constituent is called the nucleus, which is determined semantically by the second constituent, the modifier. The modifier is a special form of attribute:

This dependence of the modifier from the nucleus distinguishes genitive phrases from coordinations.

Genitive phrases are normally endocentric, which means that the nucleus (or the modifier) is the reference of the genitive phrase. For example, /bærg-e ʧenɒr/ برگِ چنار is a determining of /bærg/ برگ, and /mɒh-e ordibeheʃt/ ماهِ اردیبهشت a specification of /mɒh/ ماه.

Nevertheless, there are some exocentric qualitative genitive phrases in which neither the nucleus nor the modifier is the reference. This occurence can be noted in the following sentences (see 10•۱•d.):

کارگران دستِ خالی از اتاقِ رییس بیرون آمدند.

راه درازست و ما پایِ پیاده.

In these examples, /dæst-e xɒli/ دستِ خالی is neither /dæst/ دست nor /xɒli/ خالی, and /pɒ-je piɒdæ/ پایِ پیاده is neither /pɒ/ پا nor /piɒdæ/ پیاده.

b•a. Classifications of Genitive

The genitive can be classified in Persian as follows:

- ۱۰•۱. Qualitative Genitive

- ۱۰•۲. Substantial Genitive

- ۱۰•۳. Explicative Genitive

- ۱۰•۴. Possessive Genitive

- ۱۰•۵. Comitative Genitive

b•b. Syntax of Genitive

The following points are notable in the syntax on Persian genitive phrases:

- Genitive phrases are normally syndetical (meaning that they have a conjunction). Nevertheless, some qualitative genitive phrases are used asyndetically (often regarding to phonological reasons): /rezɒ bærɒhæni/ رضا براهنی, /mærd-i irɒni/ مردی ایرانی

Asyndetical genitive phrases are not lemmas; this feature differentiates them from synapses ↓.

- Unlike coordinations, genitive phrases cannot contain many constituents. Nevertheless, they can be interlaced:

- Genitive phrases can be used as modifiers of other genitive phrases:

رواقِ منظرِ چشمِ من [NPrævɒɣ-e [NPmænzær-e [NPʧæʃm-e mæn]]] آشیانهیِ توست

کرم نما و فرود آ! که خانه خانهیِ توست

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- Qualitative genitive phrases can also become nuclei of other genitive phrases:

سروِ چمانِ من [NP[NPsærv-e ʧæmɒn]-e mæn] چرا میلِ چمن نمیکند؟

همدمِ گل نمیشود، یادِ سمن نمیکند؟

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- Genitive phrases can be used as modifiers of other genitive phrases:

c. Determinative Composition

Determinative composition is a type of composition in which the constituents have a hierarchical relationship. These constituents are called (similarly to constituents in genitive phrases) the nucleus and modifier.

In Indo-European languages, the modifier normally prepends the nucleus:

The determinative composition is called synapsis, if the nucleus is placed in front of the modifier:

Unlike genitive phrases, determinative compounds are lemmas. This feature differentiates synapses from asyndetical genitive phrases.

c•a. Endocentric Determinative Composition

A determinative composition (in the Sanskrit grammar tatpuruṣa तत्पुरुष = “that person’s man”) is endocentric if the nucleus (or the modifier) is the reference of the composition. For example, /tut-færængi/ توتفرنگی is a determining of /tut/ توت, and /ɒtæʃ-gærdɒn/ آتشگردان a specification of /gærdɒn/ گردان.

Endocentric determinative compounds can be noted in the following cases in Persian:

- With a noun phrase as nucleus. In this case, the determinative compound is a noun phrase too:

- With an appellative-indefinite noun phrase as modifier:

- In the endocentric possessive composition. In these compositions, the nucleus belongs or appertains to the modifier (see 10•۴. Possessive Genitive): /gol-bærg/ گلبرگ, /dɒneʃ-kædæ/ دانشکده

As synapses: /doxtær-æmu/ دخترعمو, /sɒheb-del/ صاحبدل, /tæh-dig/ تهدیگ, /væli-neʔmæt/ ولینعمت, /sær-ængoʃt/ سرانگشت

Particularly possessive compounds which accept the suffix /-i/ (from the Middle Persian suffix /-ik/) are always used as synapses: /pær-kælɒɣi/ پرکلاغی, /ʧeʃm-bolboli/ چشمبلبلی, /pæs-gærdæni/ پسگردنی, /tu-guʃi/ توگوشی, /zir-sigɒri/ زیرسیگاری

- In the endocentric substantial composition. In these compositions, the modifier identifies the material of which the nucleus is made up (see 10•۲. Substantial Genitive): /zær-ængoʃtæri/ زرانگشتری, /bolur-kɒsæ/ بلورکاسه

As synapsis: /tæxtæ-sæng/ تختهسنگ

- In the endocentric explicative composition. In these compositions, the nucleus represents the class of the modifier (see 10•۳. Explicative Genitive): /tir-mɒh/ تیرماه, /ærvænd-rud/ اروندرود

Also compounds with nuclei such as /ɒɣɒ/ آقا, /xɒn/ خان, /xɒnom/ خانم and /ʃɒh/ شاه count amongst this group: /hæsæn-ɒɣɒ/ حسنآقا, /bæhrɒm-xɒn/ بهرامخان, /pærvin-xɒnom/ پروینخانم, /æhmæd-ʃɒh/ احمدشاه

As synapses: /ɒɣɒ-rezɒ/ آقارضا, /ʃɒh-rezɒ/ شاهرضا

- The attribution of nomina actionis by direct objects (see 3•d•a•b.): /molɒɣɒt-kærdæn/ ملاقاتکردن, /tæɣjir-dɒdæn/ تغییردادن

- fraction numerals in archaic idioms: /ʧɒr-jek/ چاریک, /hezɒr-jek/ هزاریک

- In the endocentric possessive composition. In these compositions, the nucleus belongs or appertains to the modifier (see 10•۴. Possessive Genitive): /gol-bærg/ گلبرگ, /dɒneʃ-kædæ/ دانشکده

- With an adjectival phrase as a modifier:

- In the endocentric qualitative composition. In these compositions, the modifier represents a feature of the nucleus (see 10•۱. Qualitative Genitive): /bozorg-rɒh/ بزرگراه, /xorræm-ʃæhr/ خرّمشهر

These compounds can be noted in the following cases as synapses:

- If the modifier ends with the suffix /-i/ (from the Middle Persian suffix /-ik/): /sib-zæmini/ سیبزمینی, /gævʤæ-færængi/ گوجهفرنگی, /doxtær-irɒni/ دخترایرانی, /kɒɣæz-divɒri/ کاغذدیواری

- In colloquial speech, features of persons (e.g. professions) can be attached to their names for differentiation purposes: /sæid-lule-keʃ/ سعیدلولهکش, /mæmmæd-læbui/ ممّدلبویی, /rezɒ-motori/ رضاموتوری, /hæsæn-kæʧæl/ حسنکچل

- Irregular: /hæjɒt-xælvæt/ حیاتخلوت

- The attribution of nomina actionis by predicative complements (see 3•d•a•b.): /bozorg-dɒʃt/ بزرگداشت, /xɒki-ʃodæn/ خاکیشدن

- fraction numerals as synapses: /jek-pænʤom/ یکپنجم, /do-sevvom/ دوسوم

- The reciprocal pronouns /hæm-digær/ (/hæm-degær/) همدیگر، همدگر, /jek-digær/ (/jek-degær/) یکدیگر، یکدگر and in archaic idioms /jek-digærɒn/ یکدیگران as synapses.

- In archaic idioms, the ordinal numerals /do-digær/ دودیگر and /se-digær/ سهدیگر as synapses.

- In the endocentric qualitative composition. In these compositions, the modifier represents a feature of the nucleus (see 10•۱. Qualitative Genitive): /bozorg-rɒh/ بزرگراه, /xorræm-ʃæhr/ خرّمشهر

- With an adverb phrase as a modifier, in the attribution of nomina actionis by verb particles (see 3•d•a•b.): /bær-xord/ برخورد, /vær-ræftæn/ وررفتن

- With an appellative-indefinite noun phrase as modifier:

- With an adjectival phrase as nucleus. Such determinative compounds are also adjectival phrases:

- With an appellative-indefinite noun phrase as a modifier:

- The attribution of nomina patientis by the following sentence constituents (see 4•۱•b.):

- Subjects: /xod-kærdæ/ خودکرده

- Instrumental adverbials: /dæst-neʃɒndæ/ دستنشانده, /xɒb-ɒludæ/ خوابآلوده

- Direct objects noun phrases: /ɒb-dɒdæ/ آبداده

- The attribution of nomina agentis by direct objects (see 4•۲•b.): /mæsræf-konændæ/ مصرفکننده, /gerjæ-konɒn/ گریهکنان

- The attribution of nomina patientis by the following sentence constituents (see 4•۱•b.):

- With another adjectival phrase as a modifier, in the attribution of nomina patientis and nomina agentis by predicative complements (see 4•۱•b. and 4•۲•b.): /bozorg-kardæ/ بزرگکرده, /nærm-konændæ/ نرمکننده

- With an adverb phrase as a modifier, in the attribution of nomina patientis and nomina agentis by verb particles (see 4•۱•b. and 4•۲•b.): /bær-gereftæ/ برگرفته, /bær-xorændæ/ برخورنده

- With an appellative-indefinite noun phrase as a modifier:

- With a non-finite verb form as a nucleus.

This case can only be noted in the substitution of nomina patientis and nomina agentis in the attribution process by non-finite verb forms. This occurence is largely specific to Iranian languages, and in Persian is relevant in the following forms:

- The substitution of nomina patientis by past participles (see 4•۱•b.):

/ɒb-roftæ/ آبرفته → /ɒb-roft/ آبرفت

/dæst-poxtæ/ دستپخته → /dæst-poxt/ دستپخت

/zær-ændudæ/ زراندوده → /zær-ændud/ زراندود

- The substitution of nomina patientis by present participles (see 4•۱•b.):

/zæʤr-koʃtæ/ زجرکشته → /zæʤr-koʃ/ زجرکش

/doxtær-poxtæ/ دخترپخته → /doxtær-pæz/ دخترپز

/ʧerk-neveʃtæ/ چرکنوشته → /ʧerk-nevis/ چرکنویس

- The substitution of nomina agentis by present participles (see 4•۲•b.):

/kɒr-færmɒjændæ/ کارفرماینده → /kɒr-færmɒ/ کارفرما

/hærzæ-gærdændæ/ هرزهگردنده → /hærzæ-gærd/ هرزهگرد

/ʃɒd-mɒnændæ/ شادماننده → /ʃɒd-mɒn/ شادمان

/dær-xorændæ/ درخورنده → /dær-xor/ درخور

- The substitution of nomina patientis by past participles (see 4•۱•b.):

c•b. Exocentric Determinative Composition

A determinative composition is exocentric (in the Sanskrit grammar bahuvrihi बहुव्रीहि = “having much rice”) if neither the nucleus nor the modifier is its reference. For example, /doʃmæn-ʃɒd/ دشمنشاد is neither /doʃmæn/ دشمن nor /ʃɒd/ شاد, and /del-morde/ دلمرده is neither /del/ دل nor /morde/ مرده. Nevertheless, the modifier also determines the nucleus in these compounds.

Exocentric determinative composition are used in Persian in the following cases:

- With a noun phrase as nucleus. In this case the determinative compound is an adjectival phrase:

- With another noun phrase as a modifier:

- In the exocentric possessive composition: /rubɒh-sefæt/ روباهصفـت

As synapsis: /gærdæn-homɒ/ گردنهما

- In the exocentric substantial composition: /sæng-del/ سنگدل

As synapsis: /pɒʃnæ-tælɒ/ پاشنهطلا

- In the exocentric explicative composition: /sorx-ræng/ سرخرنگ

- In the exocentric possessive composition: /rubɒh-sefæt/ روباهصفـت

- With an adjectival phrase as a modifier, in the exocentric qualitative composition: /pɒk-dɒmæn/ پاکدامن, /bæd-xu/ بدخو

As synapses: /ʧæʃm-ɒbi/ چشمآبی, /ɣæd-bolænd/ قدبلند

- With a prepositional phrases as a modifier; such quality compounds appear only as synapses: /guʃ be færmɒn/ گوش به فرمان, /sær be zir/ سر به زیر, /sær dær gom/ سر در گم

- Occasionally with an adverb phrase as a modifier: /hæmiʃæ-bæhɒr/ همیشهبهار

- With another noun phrase as a modifier:

- With a present participle as a nucleus. In Persian, such compounds are nomina loci (see 3•d•c.):

- With an appellative-indefinite noun phrase a as modifier:

- The subject: /ɒb-ræv/ آبرو, /dæst-ræs/ دسترس

- The direct object: /rɒh-ræv/ راهرو, /xɒk-riz/ خاکریز

- With an adverb phrase as a modifier, as a verb particle: /dær-ræv/ دررو

- With an appellative-indefinite noun phrase a as modifier:

Exocentric qualitative compounds are very varied. As described above, they normally appear with adjectival phrases as modifiers, for example with the adjective /besjɒr/ بسیار (= “many”):

از ایوانِ گشتاسپ تا پیشِ شاه

درختی گشنبیخ و بسیارشاخ

Daqiqi (10th Century AD)

However, the adjective /por/ پر can also be used with the same function, although it does not appear with the meaning “many” in Persian:

زمانی برقِ پرخنده، زمانی رعدِ پرناله

چون آن مادر ابر سوگِ عروسِ سیزدهساله

Rudaki (9th and 10th Century AD)

In addition, counting numerals can become modifiers of these compounds, although they are not adjectival phrase, but determinative phrases:

عقل با حس زین طلسمانِ دورنگ

چون محمّد با ابوجهلان به جنگ

Rumi (13th Century AD)

به سانِ سوسن اگر دهزبان شود حافظ

چو غنچه پیشِ تواش مُهر بر دهن باشد

Hafez (14th Century AD)

بحثِ بلبل برِ حافظ مکن از خوشسخنی

پیشِ توتی نتوان نامِ هزارآوا بُرد

Hafez (14th Century AD)