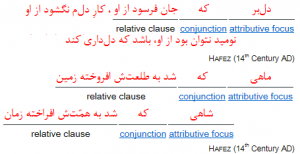

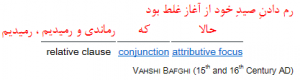

The relative clause is a subordinate clause which attributes a phrase of the main clause (i.e. attributive focus, see Chapter 10.):

The following phrases can be applied as attributive focuses of relative clauses:

| Contents |

|---|

a. Relative Pronouns

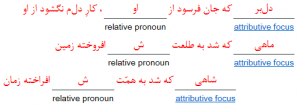

This type of subordination can be differentiated by means of its attributive focus (from the main clause) as well as a pronoun from the subordinate clause referring to the same entity. This pronoun is called relative pronoun:

As these examples demonstrate, personal and possessive pronouns are applied as relative pronouns in Persian. Demonstrative pronouns also sometimes appear with this function:

a•a. Relative Clauses without Relative Pronoun

As the discussion in this chapter demonstrates, the relative clause is used in Persian almost always (as opposed to many other Indo-European languages) syndeticalley (i.e. is accompanied by a conjunction, see below ↓). It appears that the application of the relative pronoun is remarkably less distinctive than in relative languages, and the relative clause is used without the relative pronoun if the (deleted) relative pronoun has one of the following roles:

- As the subject if the relative clause:

از آن باده که Ø زردست و Ø نزارست ولیکن

Ø نه از عشق نزارست و Ø نه از محنت زردست

Manuchehri (10th and 11th Century AD)

من که Ø شبها رهِ تقوا زدهام با دف و چنگ

این زمان سر به ره آرم؟! چه حکایت باشد؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

تو که Ø ناخواندهای علمِ سماوات

تو که Ø نابردهای ره در خرابات

تو که Ø سود و زیانِ خود ندانی

به یاران کی رسی؟! هیهات! هیهات!

Baba Taher (10th and 11th Century AD)

زاهدان کهØ این جلوه در محراب و منبر میکنند

چون به خلوت میروند آن کارِ دیگر میکنند

Hafez (14th Century AD)

However, the personal pronoun /u/ او can persist as a relative pronoun in archaic idioms:

راهی کهاو راستست، بگزین ای دوست!

دور شو از راهِ بیکرانه و ترفنج

Rudaki (9th and 10th Century AD)

هر آن کهاو برد نامِ مردم به عار

تو چشمِ نکوگویی از وی مدار!

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

- As a direct object of the relative clause. Nevertheless, the relative pronoun is not always disclaimed in this case:

این کمک به کسانی که زمینلرزه (آنان را) بیخانمان کرده، تعلّق میگیرد.

شهرداری با سگهایی که در خیابان پیدا(شان) میکند، رفتارِ ناشایستی دارد.

- As opposed to many other Indo-European languages, no relative pronouns are developed in Persian having the role of temporative or locative adverbial in relative clauses (cf. “where” and “when” in English and “wo” and “als” in German). Hence such relative clauses also appear without relative pronouns:

در جایی که کسی Ø به برادرش رحم نمیکند، نمیتوان حرف از دوستی پیش کشید.

از هنگامی که Ø با تو آشنا شده، دیگر به دوستانِ قدیمیش محلّ نمیگذارد.

بامدادان که Ø تفاوت نکند لیل و نهار

خوش بود دامنِ صحرا و تماشایِ بهار

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

امروز که Ø در دستِ تو ام مرحمتی کن!

فردا چو شدم خاک چه سود اشکِ ندامت؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

درونِ ما زِ یکی دم نمیشود خالی

کنون که Ø شهر گرفتی، روا مدار خراب!

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

Such relative clauses should not be taken for adverbial clauses (see 18•۴.), because the attributive focus can also accept other roles in the main clause as the adverbial role. In the example below, the attributive focus is the subject of the main clause:

روزی که تو را دیدم، بهترین روزِ زندگیِ من بود.

b. Position of Relative Clauses

The relative clause usually appears (accompanied by the conjunction) directly after its attributive focus. However, this rule can be disregarded in the following cases:

- If the attributive focus is accompanied by the postposition /rɒ/ را, the relative clause can be set in front of or after this postposition:

او برادرش که با او مخالفت میکرد را کشت. ⇆ او برادرش را که با او مخالفت میکرد کشت.

- To emphasis the relative clause, it can be dislocated after the predicate of the main clause (see 15•d.):

شبانِ وادیِ ایمن گهی رسد به مراد

که چند سال به جان خدمتِ شعیب کند

Hafez (14th Century AD)

من آن نگینِ سلیمان به هیچ نستانم

که گاهگاه بر او دستِ اهرمن باشد

Hafez (14th Century AD)

This syntax is also applied if the attributive focus is one of the last constituents of the main clause:

خواننده در برابرِ او خود را چون مردی مختصرجثّه میدید که زیرِ نگاهِ غولِ بلندبالایی میباشد.

Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob (20th Century AD)

c. Deletion of Conjunctions

The relative clause can be applied for the following attributive focuses with or without conjunction:

- Attributive demonstrative and distributive pronouns. There are certain determiner phrases in the 3rd person singular in Persian, which are used exclusively as attributive focus of relative clauses (see 7•۶•e. and 7•۸•b•b.). Prominent examples of attributive pronouns include the following:

- The attributive demonstrative pronoun /ɒn ʧe/ آن چه for inanimates:

به خنده گفت که: «من شمعِ جمـعم ای سعدی!

مرا از آن چه که پروانه خویشتن بکشد»

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

نشستند بر نرمریگِ کبود

به اشتاب خوردند آن چه که بود

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

بدیشان بگفت آن چه بایست گفت

همان نیز با مریم اندر نهفت

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

آن چه خواهی که مدرویش، مکار!

وآن چه خواهی که مشنویش، مگوی!

Nasir Khusraw (11th Century AD)

- The attributive distributive pronoun /hær ʧe/ (/hær ʧi/) هر چه، هر چی for inanimates:

من همان دم که وضو ساختم از چشمهیِ عشق

چارتکبیر زدم یکسره بر هر چه که هست

Hafez (14th Century AD)

تن چو خواهد گذاشت هر چه که داشت

نیکبخت آن که تخمِ نیکی کاشت

Amir Khusro Dahlavi (13th and 14th Century AD)

وز او هر چه آباد بینی بسوز!

شب آور هر آن جا که باشی به روز!

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

هیچ آدابیّ و ترتیبـی مجوی!

هر چه میخواهد دلِ تنگت، بگوی

Rumi (13th Century AD)

- The attributive distributive pronoun /hær ke/ (/hær ki/) هر که، هر کی for persons:

هر که چون سایه گشت خانهنشین

تابشِ ماه و خور کجا یابد؟!

Ebn-e Yamin (13th and 14th Century AD)

هر که بگویدت: «زِ مَه ابر چگونه وا شود؟»

باز گشا گرهگره بنـدِ قبا که: «همچون این!»

Rumi (13th Century AD)

- In archaic idioms, the attributive distributive pronoun /hær ʧun/ هر چون for qualities:

چون تو جزوِ عالمی هر چون بُوی

کلّ را بر وصفِ خود بینی سوی

Rumi (13th Century AD)

بدو گفت: «هر چون که میبنگرم

به پادافرهِ بد نه اندر خورم»

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

زن ار چه دلیرست و با زورِ دست

همان نیمِ مردست هر چون که هست

Asadi Tusi (11th Century AD)

- The attributive demonstrative pronoun /ɒn ʧe/ آن چه for inanimates:

- Also other distributive determiner phrases can appear asyndetically (= without conjunction):

هر کس (که) در زد، یادداشت کن!

هر جا (که) میروم، تو را میبینم.

- This is also valid for the noun phrase /væɣt-i/ وقتی:

وقتی (که) قانون در کشور معنا ندارد، همه چیز به سودِ زورمندان تمام میشود.

وقتی بچّه بود و به مدرسه میرفت، بچّههایِ دیگر از دیدارِ او بیزار بودند.

Bozorg Alavi (20th Century AD)

It is notable that the relative clause is not dislocated after the predicate in this case.

d. Definiteness of Attributive Focuses

One feature of Persian is that the attributive focus can become definite by the subordinate clause, accompanied by the enclitical article /-i/:

خانهای که دیروز دیدیم، مالِ برادرِ منست.

روزی که پول داشتم، همه اظهارِ دوستی میکردند.

تا جایی که بنزینمان میکشید، رفتیم.

Even definite attributive focuses can appear with this enclitical article /-i/, if the subordinate clause stands in contradiction to the main clause:

منی که تا دیروز همه جا احترامم حفظ بود، حالا باید برایِ هر چیزِ کوچکی به این و آن التماس کنم.

این خانهای که تا دیروز از بزرگترین بتکدههایِ جهان بود، امروز مرکزِ جهانِ اسلامست.

e. Mood of Relative Clauses

The relative clause is always a declarative inflectional phrase (see 15•a•b.).

However, a fine differentiation in Persian is the mood of its predicate: If a common situation is described in the relative clause, without expressing whether the described situation will definitely take place, the predicate does not appear in the indicative, but rather in the potential:

هر درختی که بکارم، چند سال بعد تبدیل به درختِ تنومندی میشود. (potential) ⇆ هر درختی که میکارم، چند سال بعد تبدیل به درختِ تنومندی میشود. (indicative)

ملّتی که ستم کشیده باشد، به حرفِ هر کسی شکّ میکند. (potential) ⇆ ملّتی که ستم کشیده است، به حرفِ هر کسی شکّ میکند. (indicative)

هنگامی که بهار بشود، درختان دوباره زندگی را آغاز میکنند. (potential) ⇆ هنگامی که بهار میشود، درختان دوباره زندگی را آغاز میکنند. (indicative)

To complete the picture, it should be remarked here that the predicates of the main and the relative clause can appear in the narrative independent from each other:

به گفتهیِ تاریخنویسان، فتحعلیشاه که قلمروِ آغامحمّدخانِ قاجار را به ارث برده بود (indicative)، بسیار به زنان علاقه داشته (narrative).

فتحعلیشاه که به گفتهیِ تاریخنویسان، بسیار به زنان علاقه داشته (narrative)، قلمروِ آغامحمّدخانِ قاجار را به ارث برد (indicative).

f. Proportional Clauses

(See also 18•۴•g. concesive Clause.)

The proportional clause is a special form of the relative clause which attributes the quantificative adverbial of the main clause, and is put into proportion to the main clause in this way.

The attributive focus of the proportional clause (= quantificative adverbial of the main clause) appears in Persian in the form of a proportional distributive pronoun (see 7•۸•b•d.). The proportional clause must be set directly after the attributive focus (with or without the conjunction /ke/ که). It is used semantically in the following two cases:

- If the process of the main clause is disproportionate to the process of the proportional clause. In other words, if a repetition or a growth of the process being described in the proportional clause, has no effect on the process of the main clause:

هر چقدر که برایش توضیح میدهم، باز سرِ حرفِ خودشست.

هر چه به او هیچ چیز نمیگویم، از رو نمیرود.

هر چه بزنیدش، جواب نمیدهد.

هر چند که میگفتند که: «تو را چه بوده است و چه میبینی؟»، البتّه جواب نداد.

From the book “Modjmal Ottavarikh va alghesas” (۱۲th Century AD)

- If both sentences are in logical proportion to each other, so that either the repetition or the modification of the intensity of the process, being described in the proportional clause causes a modification of the intensity of the process of the main clause. In this case, both sentences are equipped with adjectival phrases in the comparative:

هر چه به او کمتر اهمّیّت بدهیم، خشمگینتر میشود.

میوهها هر چه رسیدهتر باشند، ارزشِ خوراکیِ بیشتری دارند.

هر انـدازه به او نزدیکتر میشدم، کمتر از کارهایش سر در میآوردم.

هر چند پیشتر رود، به گمراهی نزدیکتر باشد.

Nasrollah Monshi (12th Century AD)