Predicate is the central sentence constituent and represents the process or the state which is covered by the sentence. In Persian, only verb phrases can act as predicates.

| Contents |

|---|

a. Concord and Discord of Predicates

a•a. Concord and Discord in the Number

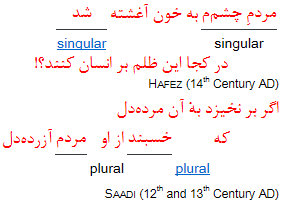

Concord in the number means that the subject and the predicate are in the same number subcategory in a sentence:

Discord in the number describes the case if the number of a predicate does not match to the quantity of entities the action or situation is assigned to. This occurence is regularly noted in modern idioms of Persian, in the following cases:

-

Plural of majesty: Discord in the number for single persons in the singular, for respect:

حضرتِ خواجهیِ ما اگر به منزلِ درویشی میرفتند، جمیعِ فرزندان و متعلّقان و خادمانِ او را پرسش میکردند.

From the book “Anis ol-Talebin” of Salah Bukhari (14th Century AD)

و چون حضرتِ امیر به شهرِ سمرقند در آمدند، به حسبِ اتّفاق گذرِ ایشان بر درِ ارک افتاده.

Khond Mir (16th Century AD)

-

Plural of modesty: Discord in the number for the 1st person singular, as a sign of modesty:

یاد آن وقت که ما دلشده را یاری بود

هر کسی را به سرِ کویِ کسی کاری بود

Hayati Gilani (17th Century AD)

-

One feature of Persian language is the optional discord in the number for inanimates in the plural:

رمزوان و داذین و دوان چند نواحی است از اعمالِ اردشیرخوره، و همه گرمسیر است.

Ebn-e Balkhi (11th and 12th Century AD)

جز در دلِ خاک هیچ منزلگه نیست

می خور! که چنین فسانهها کوته نیست

Omar Khayyam (11th and 12th Century AD)

نه دهقان، نه ترک و نه تازی بود

سخنها به کردارِ بازی بود

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

سایهیِ طوبی و دلجوییِ حور و لبِ حوض

به هوایِ سرِ کویِ تو برفت از یادم

Hafez (14th Century AD)

-

Another feature of this language is that the following pronouns appear in the 3rd person singular, while the predicate conforms to the number and the person of the superset and can cause a verbal discord:

- Distributive pronouns (see 7•۸•b•a.):

هر یک در گوشهای سنگر بگیرید!

هر کدام در کشوری از جهان به سر میبریم.

- Inexistential pronouns (see 7•۱۰•b.):

هیچ یک نایِ حرف زدن نداشتیم.

هیچ کدام تمایلی به این کار ندارید.

- Selective pronouns (see 7•۱۱.):

یک کدام به مادرتان کمک کنید!

یک کدام جانشینِ آقایِ رییس میشویم.

It is interesting that the predicate becomes concordant (in the 3rd person singular), if the superset attributes the pronoun as an origative adverbial:

یک کدام از شما به مادرتان کمک کند!

از ما کارمندانِ قدیمی یک کدام جانشینِ آقایِ رییس میشود.

هر یک از شما در گوشهای سنگر بگیرد!

از ما ایرانیان هر کدام در کشوری از جهان به سر میبرد.

هیچ یک از ما نایِ حرف زدن نداشت.

هیچ کدام از شما تمایلی به این کار ندارد.

- Distributive pronouns (see 7•۸•b•a.):

In addition, the following discords in the number can be noted in archaic idioms of Persian:

-

Discord in the number for animates in the plural:

آدم و حوّا بمرد و نوح و ابراهیمِ خلیل بمرد.

Attar Nishapuri (12th and 13th Century AD)

یکی پاکخوان از درِ مهتران

خورشها بیاراست خوالیگران

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

-

The predicate of the second conjunct is used in singular, if both sentences have the same subject in the plural in copulative coordination of inflectional phrases:

هر دیهی را چند نوبت کشش و غارت کردند و سالها آن تشویش بر داشت.

Djovaini (13th Century AD)

چون نیمهشب بود بار بر نهادند و برفت.

Balami (10th Century AD)

- The attributive distributive pronoun /hær ke/ هر که is in the singular, but it is also used with predicates in the plural (see 7•۸•b•b.):

بدان که هر که در لشکرِ تو اند، بر تو جاسوسانند!

Nasrollah Monshi (12th Century AD)

به هندوستان هر که دانا بُدند

به گفتار و دانش توانا بُدند

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

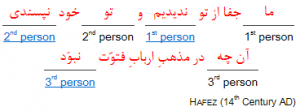

a•b. Concord and Discord in the Person

Concord in the person means that the subject and the predicate are in the same person subcategory in a sentence:

As discussed above, the following pronouns appear in Persian in the 3rd person singular, while the predicate conforms to the number and the person of the superset and can cause a discord in the person:

- Distributive pronouns (see 7•۸•b•a.):

هر یک از راهِ دیگری برایِ سرافرازیِ کشور تلاش میکنیم.

هر کدامتان داستانی دیگر برایم تعریف میکنید.

- Inexistential pronouns (see 7•۱۰•b.):

هیچ یک پاسخی به این پرسش نداشتیم.

هیچ کدام دچارِ بیخوابی نیستید.

- Selective pronouns (see 7•۱۱.):

باید یک کدام این خبر را به او بدهیم.

یک کدامتان او را لو دادهاید.

However, the predicate becomes concordant (in the 3rd person singular), if the superset attributes the pronoun as an origative adverbial:

باید یک کدام از ما این خبر را به او بدهد.

از شماها یک کدام او را لو داده است.

هر یک از ما ایرانیان از راهِ دیگری برایِ سرافرازیِ کشور تلاش میکند.

هر کدام از شما داستانی دیگر برایم تعریف میکند.

هیچ یک از ما فرزندان پاسخی به این پرسش نداشت.

هیچ کدام از شما دختران دچارِ بیخوابی نیست.

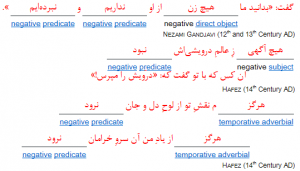

a•c. Concord and Discord in the Polarity

One feature of Persian language is the concord in the polarity: The predicate must be a negative verb phrase, as soon as any noun phrase in the sentence is negative, or the adverb /hærgez/ (/hærgiz/, /hægerz/) appears in that (as temporative adverbial):

On the other hand, two forms of discord in the polarity exist in Persian:

- Discord with affirmative predicates:

This constellation which is valid in most Indo-European languages is seldom noted in Persian literature (probably only owing to metrical conformation, see 7•۱۰•b.):

مگر میرفت استادِ مهینه

خری میبرد، بارش آبگینه

یکی گفتش که: «بس آهستهکاری

بدین آهستگی بر خر چه داری؟»

«چه دارم؟» گفت: «دل پُرپیچ دارم

که گر خر میبیفتد هیچ دارم»

Attar Nishapuri (12th and 13th Century AD)

This discord should be distinguished of the case in which nominal inexistential pronouns and inexistential determiner phrases refer to negligibly small subsets for the exaggeration and are therefore affirmative:

و گر هیچ خویِ بد آرد پدید

به سانِ پدر سرش باید برید

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

گر هیچ سخن گویم با تو زِ شکر خوشتر

سد کینه به دل گیری، سد اشک فرو باری

Manuchehri (10th and 11th Century AD)

این همه گفتیم، لیک اندر بسیچ

بی عنایاتِ خدا هیچیم، هیچ

Rumi (13th Century AD)

مرا در شعر گویی هیچ کس داشت

پس آن گه هیچ کس را داد هیچی

Suzani Samarqandi (12th Century AD)

(/hiʧ kæs/ هیچ کس in the last verse is even definite!)

- Discord with negative predicates:

This constellation only occurs if the sentence includes no indefinite noun phrases:

درویش را نباشد برگِ سرایِ سلطان

ماییم و کهنهدلقی کهآتش در آن توان زد

Hafez (14th Century AD)

دل بنهند بر کَنی، توبه کنند بشکنی

این همه خود تو میکُنی، بی تو به سر نمیشود

Rumi (13th Century AD)

a•d. Concord and Discord with the Sentence

The grammatical subcategories of a sentence normally concord with the subcategories of its predicate. A discord can only be found in the following cases:

- Discord in the polarity in rhetorical questions (see 15•a•b.):

حاشا که من به موسمِ گل ترکِ مِی کنم

من لافِ عقل میزنم، این کار کی کنم؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

(= هرگز این کار نکنم.)

کجا توانمت انکارِ دوستی کردن؟!

که آبِ دیده گواهی دهد به اقرارم

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

(= انکارِ دوستیت نتوانم کردن.)

- Negative sentences with negative adverbials (see 13•۵•a.):

چون تو را دید زردگونه شده

سرد گردد دلش، نه نابیناست

Rudaki (9th and 10th Century AD)

که: «ای بلندنظر! شاهبازِ سِدره نشین!

نشیمنِ تو نه این کنجِ محنتآبادست»

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- Sentences in the imperfective with imperfective adverbials (see 14•۱•b.):

همی در به در خشکنان باز جست

مر او را همین پیشه بود از نخست

Abu-Shakur Balkhi (10th Century AD)

در عریش او را یکی زائر بیافت

کهاو به هر دو دست می زنبیل بافت

Rumi (13th Century AD)

- Predicates of imperative sentences are normally verb phrases in the imperative. However, such verb phrases can also appear in the indicative:

میروی هر جوری شده پیدایش میکنی و میآوریش این جا!

This form indicates that the speaker is certain that the addressees attend his orders.

b. Special Forms of Predicates

b•a. Using Infinitives and Past Participles as Predicates (Infinitus)

Infinitives can be used in Indo-European languages as predicates, if the statement does not refer to a certain subject. In this case, such verb phrases have neither a number nor a person, and also no mood can be assigned to them. Such a predicate is called infinitus.

In Old Persian, the infinitive with the benefactive suffix /-æij/ played the role of infinitus. It appears in some positions in Behistun inscription: /nipæiʃtænæij/, /kætænæij/ (/kæntænæij/), /kærtænæij/, /dehistænæij/.

In New Persian, this case is still noted in archaic idioms:

شاید پسِ کارِ خویشتن بنشستن /benʃæstæn/

لیکن نتوان زبانِ مردم بستن /bæstæn/

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

نشاید به دستان شدن /ʃodæn/ در بهشت

که بازت رود چادر از رویِ زشت

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

However, this role is accepted in modern idioms by the past participle. As mentioned, infinitus is used, if the statement does not refer to a certain person:

ما باید همه چیز را به او بگوییم (affirmative 1st person plural) ⇆ باید همه چیز را به او گفت (affirmative past participle)

او باید دست به هیچ چیز نزند (negative 3rd person singular) ⇆ باید دست به هیچ چیز نزد (negative past participle)

The infinitus is used in Persian only in content clauses. The tense of the verb phrase is equal to the tense of the verb phrase in the main clause:

- ۱۸•۲•e•a•a. Content clause of an intransitive modal verb with the infinitive /ʃodæn/ شدن:

زندگی را میشود احساس کرد.

- ۱۸•۲•e•a•b. Content clause of an intransitive modal verb with the infinitive /bɒjestæn/ بایستن:

که لهراسب را شاه بایست خواند

وز او در جهان نامِ شاهی براند

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

- ۱۸•۲•e•a•c. Content clause of an intransitive modal verb with the infinitive /ʃɒjestæn/ شایستن:

نشاید به دارو دوا کردشان

که کس مطّلع نیست بر دردشان

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

- ۱۸•۲•e•b•a. Content clause of a itransitive modal verb with the infinitives /tævɒestæn/ توانستن or /tævɒestæn/ تانستن:

میتوان تنها به حلِّ جدولی پرداخـت.

Forough Farrokhzad (20th Century AD)

- ۱۸•۲•e•b•b. Content clause of a transitive modal verb with the infinitive /jɒrestæn/ یارستن:

که گویند: «از ایران سواری نبود

که یارست با شیده رزم آزمود»

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

- ۱۸•۲•e•b•c. Content clause of a transitive modal verb with the infinitive /xɒstæn/ خواستن:

It appears that the future tense in Indo-European languages is originally a subordination with content clause, which is felt by most speakers as a consistent verb phrase by the grammaticalization. In Persian, modal verbs with the infinitive /xɒstæn/ خواستن are used for this aim:

- The indicative future (see 14•۱•e.):

مرا مهرِ سیهچشمان زِ سر بیرون نخواهد شد

قضایِ آسمانست این و دیگرگون نخواهد شد

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- The indicative post-past (see 14•۱•g.):

آن روز که بامداد سلطان به فتحِ خلیج بیرون خواستی شد، ده هزار مرد به مزد گرفتند.

Nasir Khusraw (11th Century AD)

Because of this grammaticalization, the two constituents are not separable in Persian.

- The indicative future (see 14•۱•e.):

b•b. Using Perfect Participles as Predicates

In the copulative coordination of two sentences having the same subject and happening sequentially, the predicate of the first conjunct can be used in the shape of a perfect participle (see 17•a.), whereas the coordination can be used asyndetically:

پیرمرد فریادی کشیده، آناً مرد.

Modjtaba Minavi (20th Century AD)

وقایعِ عمدهیِ آن سال را بعضیها در یک کتاب نوشته، انتشار میدهند.

Ali-Akbar Dehkhoda (19th and 20th Century AD)

آب بعد از این که به این حوضها میرسید از آنها جاری شده، بیرون میآمد.

Modjtaba Minavi (20th Century AD)

Such a perfect participle is in the same predicative subcategories as the predicate of the second conjunct.

c. Deletion of Predicates

The predicate can be deleted in the following situations:

- Suppletive verbs and verb phrases from the infinitive /budæn/ بودن (as copulative predicates) in the following cases:

- In imperative and optative sentences:

سفر به خیر (باد)!

لعنت بر شیطان (باد)!

ساکت (باش، باشید)!

خدا حافظ (باد)!

خاموش! که خاموشی بهتر زِ عسلنوشی

در سوز عبارت را! بگذار اشارت را!

Rumi (13th Century AD)

- For emphasis:

به تاری گردنش را بسته زلفت

فقیر و عاجز و بیدست و پا دل!

Abolqasem Lahouti (19th and 20th Century AD)

طالع اگر مدد کند، دامنش آورم به کف

گر بکشم زهی طرب! ور بکشد زهی شرف!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

بس کس که به مالِ نو کند دستدرازی!

بس کس که به جاهِ تو کند دشمنمالی!

Suzani Samarqandi (12th Century AD)

خنک نیکبختی که در گوشهای

به دست آرد از معرفت توشهای

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

- If the predicative complement is an adjectival exclamative phrase:

چه قشنگ (است)!

چه خوب (است) که تو هم میآیی!

چه عجب (است)!

چه بسیار (ند) کودکانی که دچارِ مالاریا هستند!

- The predicate must be deleted, if the subject or the predicative complement is an exclamative phrase with a determinativized adposition (see 7•۱۵•c.):

خوشا شیراز و وضعِ بیمثالش!

خداوندا! نگهدار از زوالش!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

ای خوشا دولتِ آن مست که در پایِ حریف

سر و دستار نداند که کدام اندازد!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

دریغا که بر خوانِ الوانِ عمر

دمی خورده بودیم و گفتند: «بس!»

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

بسا عقلِ زورآورِ چیردست

که سودایِ عشقش کند زیردست!

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

بسا تلخعیشان و تلخیچشان

که آیند در حلّه دامنکشان

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

ای بسا هندوّ و ترکِ همزبان!

ای بسا دو ترک چون بیگانگان!

Rumi (13th Century AD)

ای بسا ابلیسِ آدمرو که هست!

پس به هر دستی نشاید داد دست

Rumi (13th Century AD)

خندهیِ جامِ می و زلفِ گرهگیرِ نگار

ای بسا توبه که چون توبهیِ حافظ بشکست!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

بسا که مست در این خانه بودم و شادان!

چنان که جاهِ من افزون بُد از امیر و ملوک

Rudaki (9th and 10th Century AD)

بسا که خندان کردهست چرخ گریان را!

بسا که گریان کردهست نیز خندان را!

Nasir Khusraw (11th Century AD)

بس اندکسپاها که روزِ نبرد

زِ بسیار لشگر بر آورد گرد

Asadi Tusi (11th Century AD)

- If the noun /kɒʃ/ کاش, /kɒʧ/ کاچ, /kɒʤ/ کاج or /kɒʃki/ کاشکی (with the meaning “well”?) occurs either in isolation or in the shape of a adpositional phrase with the preposition /æj/ ای in the function of the predicative complement, the predicate must always be deleted:

کاش پولم تا آخرِ ماه برسد!

ای کاش که جایِ آرمیدن بودی!

یا این رهِ دور را رسیدن بودی!

Omar Khayyam (11th and 12th Century AD)

مرا کاچ هرگز نپروردهای!

چو پرورده بودی نیازردهای!

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

کاج بیرون نیامدی سلطان!

تا ندیدی گدایِ بازارش

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

آن کهاو تو را به سنگدلی گشت رهنمون

ای کاشکی که پاش به سنگی بر آمدی!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- In imperative and optative sentences:

- For vowing or for conjuring. In this case the actional object can also be deleted together with the predicate:

به جان شما سوگند میخورم…

به جان شما سوگند …

به جان شما …

تو را به جانِ عزیزانت قسم میدهم …

تو را به جانِ عزیزانت قسم …

تو را به جانِ عزیزانت …

قسم به حشمت و جاه و جلالِ شاه شجاع

که نیست با کسم از بهرِ مال و جاه نزاع

Hafez (14th Century AD)

به سرت گر همه عالم به سرم جمـع شوند

نتوان برد هوایِ تو برون از سرِ ما

Hafez (14th Century AD)

دل میرود زِ دستم، صاحبدلان! خدا را

دردا که رازِ پنهان خواهد شد آشکارا

Hafez (14th Century AD), see 15•۴•l.

- To express sorrow, surprise, satisfaction and other emotions, if the actional object is an onomatopoetic like /ɒh/ آه, /vɒj/ وای, /ɒvæx/ آوخ, /bæh/ به or /bæh-bæh/ بهبه or a nomen actionis like /færjɒd/ فریاد, /dɒd/ داد, /æmɒn/ امان, /æfsus/ افسوس, /ɒfærin/ آفرین, /moʒdæ/ مژده etc, and the predicate is used in the 1st person:

امان (میخواهم) از دستِ کارهایِ تو!

گر مسلمانی از اینست که حافظ دارد

وای (میگویم)، اگر از پسِ امروز بود فردایی!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

دوش میسوختم در این آتش

آه (میکشم)، اگر امشبم بُوَد چون دوش!

Hatef Esfahani (17th and 18th Century AD)

فریاد (میکشم)! که از شش جهتم راه ببستند

آن زلف و رخ و خال و خط و عارض و قامت

Hafez (14th Century AD)

مژده (میدهم) ای دل! که مسیحانفسی میآید

که زِ انفاسِ خوشش بویِ کسی میآید

Hafez (14th Century AD)