A sentence (category symbol: S) is a statement referring to executing a process or having a state (the predicate), usually by an entity (the subject). Each sentence can consist of one or several sentence constituents ↓.

| Contents |

|---|

a. Grammatical Categories of Sentences

a•a. Valency of Sentences

The term valency originates from chemistry, and in grammar it describes the number of sentence constituents ↓ exclusive of the predicate in a sentence:

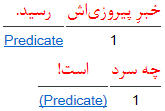

- An avalent sentence consists only of the predicate and does not need any subject, object or predicative. Such sentences are not used in Persian (see 15•۲. impersonal sentence).

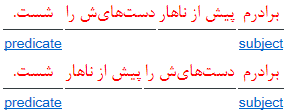

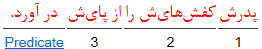

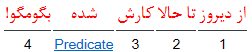

- Monovalent sentences, normally with the subject:

Please note that the subject increases the valence, even if it is deleted from the sentence:

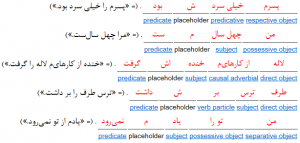

- Divalent sentences:

- Trivalente sentences:

- Tetravalent sentences:

- And so on…

a•b. Sentence Mood

The grammatical category sentence mood refers to the effect or the reaction that the speaker aims to achieve with that sentence.

The mood of a sentence is closely related to the mood of its predicate, although these grammatical categories do not completely cover each other:

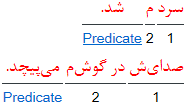

- Declarative sentences express the existence of a process or a state:

سرم درد میکند.

من نمیخواستم که به دبیرستان بروم.

A special form of declarative sentences is called an exclamative sentence. It expresses in addition the wondrousness of the speaker:

خیلی گستاخ شدی ها!

چه بانمک!

- Interrogative sentences inquire about the existence or the modalities of a process or a state:

بیداری؟

قطار ساعتِ چند خواهد رسید؟

These sentences can be classified as follows:

- Polarity interrogatives ask whether the statement of the sentence is valid (they ask about the polarity of the sentence ↓). Such sentences are used in the simple form or with an disjunctive adverbial, and should be answered by “yes” or “no”:

آیا شما حاضر هستید به خاطرِ رفاهِ مردم از فرمانروایی چشمپوشی کنید؟

پدرت سرِ کارست؟

من که شبها رهِ تقوا زدهام با دف و چنگ

این زمان سر به ره آرم؟! چه حکایت باشد؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- A disjunctive interrogative asks which one of the conjuncts (out of a disjunctive coordination) the statement is valid for. Such questions cannot be answered by “yes” or “no”:

امروز میرسد یا فردا؟

به خودش زنگ زدی یا به پدرش؟

- Constituent interrogatives inquire about a phrase from the sentence. In this case, this phrase is replaced by an interrogative pronoun:

کی دمِ در بود؟

فروشگاه تا کی بازست؟

- Polarity interrogatives ask whether the statement of the sentence is valid (they ask about the polarity of the sentence ↓). Such sentences are used in the simple form or with an disjunctive adverbial, and should be answered by “yes” or “no”:

- Processes or states can be demanded by imperative sentence:

به خانه برو!

برایش یک لیوان بیاورید!

- An optative sentence expresses a wish:

مبادا از پا افتاده باشد!

پاینده ایران!

The following points are notable for the sentence mood:

- Predicates of declarative and interrogative sentences can be verb phrases in every mood subcategory, except in the imperative and the optative.

- Predicates of imperative sentences are normally verb phrases in the imperative. However, such verb phrases can also appear in the indicative:

میروی هر جوری شده پیدایش میکنی و میآوریش این جا!

This form indicates that the speaker is sure that the addressees attend his orders.

- Predicates of optative sentences are verb phrases in the optative.

- A special type of declarative sentences is the rhetorical question. It has the syntax of interrogative sentences (e.g. with disjunctive adverbials and pronouns), but does not have the purpose to gather information. Instead, it shows the expectation that addressees should consider the statement as false, like the speaker does too:

چه نسبتست به رندی صلاح و تقوا را؟!

سماعِ وعظ کجا، نغمهیِ رباب کجا؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

(= صلاح و تقوا را نسبتی به رندی نیست. سماعِ وعظ و نغمهیِ رباب را در یک جا نمیتوان یافت.)

چه کارست پیشِ امیرم؟! که دانم

که گر میر پیشم نخواند نمیرم

Nasir Khusraw (11th Century AD)

(= پیشِ امیر مرا کاری نیست.)

ما که به سیراب زمین کاشتیم

زآن چه بکشتیم چه بر داشتیم؟!

Nezami Gandjavi (12th and 13th Century AD)

(= ما از آن چه بکشتیم چیزی بر نداشتیم.)

حاشا که من به موسمِ گل ترکِ مِی کنم

من لافِ عقل میزنم، این کار کی کنم؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

(= هرگز این کار نکنم.)

کجا توانمت انکارِ دوستی کردن؟!

که آبِ دیده گواهی دهد به اقرارم

Saadi (12th and 13th Century AD)

(= انکارِ دوستیت نتوانم کردن.)

Consequently, a kind of discord in the polarity appears: The polarity ↓ of the rhetoric question is opposed to the polarity of its predicate.

- The sentence constituents ↓ which also appear in the question can be deleted from the answer:

– کی حاضر میشوی؟

– پنج دقیقهیِ دیگر (حاضر میشوم).

– چرا قرصِ مسکّن میخوری؟

– چون سرم درد میکند (قرصِ مسکّن میخورم).

This fact leads to the case that (when answering to a polarity interrogative), the answer consists only of an adverbial:

- The accentual adverbials /ɒri/ آری and /ɒre/ آره as well as /bæli/ بلی and /bæle/ بله are used to confirm affirmative questions:

– هیچ به غذا سر زدهای؟

– آره.

– آیا همه چیز را برایِ او تعریف میکنی؟

– بله که همه چیز را برایِ او تعریف میکنم.

(see 18•۲. Complement Clause)

- The negative adverbials /næ/ نه and /ni/ نی as well as /næ xæjr/ نه خیر and /xæjr/ خیر are applied to deny affirmative questions or to confirm negative questions:

– آیا برایِ برادرت نامه نوشتهای؟

– نه.

چو من دستگه داشتم هیچ وقت

زبانِ مرا عادتِ «نه» نبود

Masud Saad Salman (11th and 12th Century AD)

نی! نی! غلطم، که خود فراقِ تو مرا

کی زنده رها کند که بازم بینی؟!

Rumi (13th Century AD)

- The interrogative pronoun /ʧe-rɒ/ چرا as a causal adverbial. This postpositional phrase is used as grammaticalization of the rhetorical question “why do you think so?” to deny negative questions:

– مگر نامهیِ من به دستت نرسیده؟

– چرا.

- The accentual adverbials /ɒri/ آری and /ɒre/ آره as well as /bæli/ بلی and /bæle/ بله are used to confirm affirmative questions:

a•c. Other Grammatical Categories of Sentences

All other grammatical categories of verb phrases can also be noted for sentences (see 13•c.).

The grammatical subcategories of a sentence usually concord with the subcategories of its predicate. A discord can be found only in the following cases:

- Discord in the polarity in rhetoric questions (see above).

- Negative sentences with negative adverbials (see 13•۵•a.):

چون تو را دید زردگونه شده

سرد گردد دلش، نه نابیناست

Rudaki (9th and 10th Century AD)

که: «ای بلندنظر! شاهبازِ سِدره نشین!

نشیمنِ تو نه این کنجِ محنتآبادست»

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- Sentences in the imperfective with imperfective adverbials (see 14•۱•b.):

همی در به در خشکنان باز جست

مر او را همین پیشه بود از نخست

Abu-Shakur Balkhi (10th Century AD)

در عریش او را یکی زائر بیافت

کهاو به هر دو دست می زنبیل بافت

Rumi (13th Century AD)

b. Inflectional Phrases

Inflectional phrase (category symbol: IP) is the genus for simple sentences and combined sentence complexes.

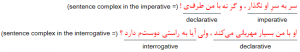

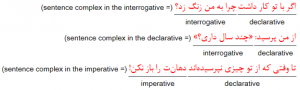

Sentence complexes can be classified as follows:

Sentence complexes and sentences only have the sentence mood in common as grammatical category. The following points are notable here:

- If a conjunct from a coordination of inflectional phrases is in the imperative or interrogative, the whole coordination is also in the imperative or interrogative, respectively:

Otherwise the sentence complex is in the declarative. - A subordination has the same sentence mood like its main clause:

c. Sentence Constituents

Sentence constituents are phrases, of which sentences consist. Each sentence constituent has a special function in the sentence.

Persian sentence constituents are:

- ۱۵•۱. Predicates

- ۱۵•۲. Subjects

- ۱۵•۳. Objects

- ۱۵•۴. Adverbials

- ۱۵•۵. Predicative Complements

- ۱۵•۶. Vocatives

- As well as placeholders ↓

d. Word Order and Dislocation

Word order describes the arrangement of constituents within a sentence.

Languages are classified typologically by the order of predicate (P), subject (S) and object (O) in declarative sentences. Persian is (like Latin, Japanese, Korean, Turkish, Hungarian and Indo-Aryan languages) among the so-called “SOP” languages by means of this classification, i.e. the declarative sentence normally begins with the subject and ends with the predicate. The word order of the other sentence constituents between them is relative free in this language:

One is confronted with the occurence dislocation in Persian, if another constituent is set at the onset or end of the declarative sentence. Dislocation is optional and normally happens for semantic reasons (e.g. accentuation):

- Dislocation behind the predicate:

- The directive adverbial can be dislocated behind the predicate. It appears in this case as a noun phrase (without adposition):

ده هزار طاقه از مستعملاتِ آن نواحی بدهند بیرون.

Abolfazl Beyhaqi (10th and 11th Century AD)

داشتم سوارِ تاکسی میشدم تا بر گردم خانه.

Jalal Al-e Ahmad (20th Century AD)

The semantic benefit of this dislocation is to stress the difference between locative and directive adverbials:

- Directive adverbial: کیفش را رویِ میز گذاشت. ⇆ کیفش را گذاشت رویِ میز.

- Locative adverbial: کیفش رویِ میز جا ماند. ⇆ Ø

- If an indefinite qualitative genitive phrase is placed directly in front of the predicate, its modifier can be dislocated behind the predicate (see 10•۱•b.):

مردی غولپیکر دیدم. ⇆ مردی دیدم غولپیکر.

فلکِ گردان شیریست رباینده

که همی هر شب زی ما به شکار آید

Nasir Khusraw (11th Century AD)

دیگر روز باری داد سخت باشکوه.

Abolfazl Beyhaqi (10th and 11th Century AD)

Whenever the modifier is a coordination, only its first conjunct may remain ahead of the predicate:

گلستان از لحاظِ نویسندگی اثری ممتازست و قابلِ توجّه.

Gholam Hossein Yusefi (20. Jh. n. Chr.)

This kind of dislocation happens without any semantic effect to a large extent.

- To emphasis the relative clause, it can be dislocated after the predicate of the main clause (see 18•۱•b.):

شبانِ وادیِ ایمن گهی رسد به مراد

که چند سال به جان خدمتِ شعیب کند

Hafez (14th Century AD)

من آن نگینِ سلیمان به هیچ نستانم

که گاهگاه بر او دستِ اهرمن باشد

Hafez (14th Century AD)

This syntax is also applied if the attributive focus is one of the last constituents of the main clause:

خواننده در برابرِ او خود را چون مردی مختصرجثّه میدید که زیرِ نگاهِ غولِ بلندبالایی میباشد.

Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob (20th Century AD)

- In addition, the content clause is typically dislocated after the predicate of the main clause (see 18•۲•b.):

مجالِ من همین باشد که پنهان عشقِ او ورزم

کنار و بوس و آغوشش چگونه، چون نخواهد شد؟!

Hafez (14th Century AD)

از آن به دیرِ مغانم عزیز میدارند

که آتشی که نمیرد همیشه در دلِ ماست

Hafez (14th Century AD)

- The directive adverbial can be dislocated behind the predicate. It appears in this case as a noun phrase (without adposition):

- Dislocation in front of the subject:

- If the subject is a possessive genitive phrase, the modifier can be dislocated in front of the subject. In this case, an enclitical possessive pronoun appears a placeholder (cf. 4•f. Placeholder in Focus Shifting of Adjectival Phrases and 18•۲. Placeholder of Content Clause):

کتابِ من گم شده. ⇆ من کتابم گم شده.

سرِ بهرام درد میکند. ⇆ بهرام سرش درد میکند.

نصفِ این سیب خرابست. ⇆ این سیب نصفش خرابست.

کارِ شما بیشتر از اینها طول میکشد. ⇆ شما کارتان بیشتر از اینها طول میکشد.

As the examples above illustrate, in Persian there is a dislocational concord in the number and in the person: The dislocated constituent and its placeholder are always in the same subcategory of number and person, respectively.

- There are sentences in Persian which are always in the 3rd person singular, having an enclitical possessive pronouns as object (see 15•۲. impersonal sentence).

A feature of such sentences is that the object is felt as an agent of the action, not the subject. Therefore, one tends to dislocate this agent in front of the grammatical subject (as a noun phrase:

As these examples demonstrate, the enclitical possessive pronoun serves as a placeholder here.

- Sentence constituents can be dislocated in front of the subject in order to express them:

ناگهان صدایِ گریهیِ بچّه بلند شد.

پس از سخنرانی همه خشکشان زده بود.

رویِ درخت پرندهای نشسته بود.

The examples above make it clear that such dislocations need no placeholder. However, if the direct object is dislocated, it can be deputized by an enclitical possessive pronoun as a placeholder:

حسین را حسابی کتکش زدهاند.

کیخسرو بعد از آن درگاهِ ایزد گرفتش.

Balami (10th Century AD)

- If the subject is a possessive genitive phrase, the modifier can be dislocated in front of the subject. In this case, an enclitical possessive pronoun appears a placeholder (cf. 4•f. Placeholder in Focus Shifting of Adjectival Phrases and 18•۲. Placeholder of Content Clause):

Owing to metrical conformation, the word order can be handled very freely in the Persian lyric and its rules can be disregarded:

بود شاهی، شاه را بُد سه پسر

هر سه صاحبفطنت و صاحبنظر

Rumi (13th Century AD)

پراکند گردِ جهان موبدان

نهـاد از برِ آذران گنبدان

Ferdowsi (10th and 11th Century AD)

Not only can the order of the sentence constituents be changed, but also constituents of a sentence constituent can be discerped. For example it is commonly used that the object is attached to the cardinal numeral of numeral phrases, if the object is an enclitical possessive pronoun (see 6•۱•۱•b):

رویِ تو کس ندید و هزارت رقیب /hezɒr-æt ræɣib/ هست

در غنچهای هنوز و سدت عندلیب /sæd-æt ændælib/ هست

Hafez (14th Century AD)

کُشتهیِ چاهِ زنخدانِ توام، کهاز هر طرف

سد هزارش گردنِ جان /sæd hezɒr-æʃ gærdæn-e ʤɒn/ زیرِ طوقِ غبغبست

Hafez (14th Century AD)